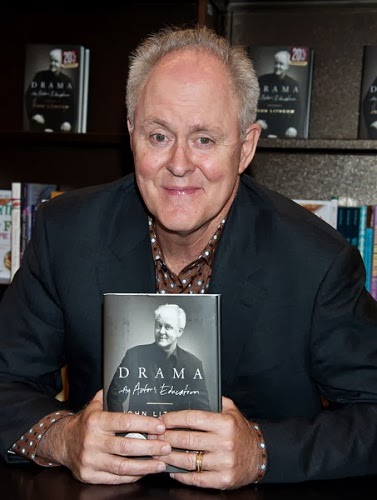

Audiobook addict that I am, I recently downloaded John

Lithgow’s 2011 memoir entitled Drama: An

Actor’s Education. I had been on the fence about choosing it until I

sampled the book’s preface (by the author and available in its entirety on the Kindle

edition page), which hooked me with a very personal and surprisingly moving

story.

Lithgow, now 58, is perhaps best-known for the ‘90s sitcom Third Rock from the Sun and more

recently from the decidedly un-sitcom-y series Dexter. He not only has a long, distinguished career in Hollywood

and the theater, but he also has created music and books for children, in

addition to writing the autobiography Drama.

In other words, his life’s work has been, in one form or another, the telling

of stories.

In the book’s preface, Lithgow relates how he went to live

with his parents in their Amherst, Massachusetts condo in the summer of 2002 to

help care for his frail, 86-year-old father, recovering from surgery. The most

difficult aspect to manage was his father’s deep depression; he seemed to have

lost the will to live, despite Lithgow’s desperate efforts to cheer him up. Lithgow

felt he was helplessly watching his father’s slow, inevitable slide toward

death – until the actor drew upon his childhood memories for an idea.

As a boy, Lithgow and his siblings curled up every night for

Story Hour as their father read to them from Kipling, Dickens, Carroll, and

more. Some of his most intimate memories of his father, Lithgow writes, stem

from those “lazy, luxurious evening hours on that scratchy wool sofa.” Most

memorable was a massive 1939 tome called Tellers

of Tales, comprising one hundred classic short stories; the family’s

favorite among them was an hilarious P.G. Wodehouse piece called “Uncle Fred

Flits By.”

Fifty years later, Lithgow searched for and found Tellers of Tales among his parents’

possessions. He offered to read something to them from it that night. Sure

enough, they requested “Uncle Fred Flits By.” The theatrically-trained Lithgow threw

himself into the tale, and before long his father was laughing helplessly and

breathlessly. “I am convinced,” Lithgow writes in his preface, “that it was

sometime during the telling of that story that my father came back to life”:

Acting is nothing more than

storytelling… Reading to my parents on that autumn evening in Amherst… was

acting in its simplest, purest, most rarefied form. My father was listening to

“Uncle Fred Flits By” as if his life depended on it. And indeed, it did. The

story was not just diverting him. It was easing his pain, dissolving his fear,

and bringing him back from the brink of death. It was rejuvenating his

atrophied soul.

Afterward, his father thanked Lithgow for that precious

gift; his health and good spirits returned and he lived another eighteen months,

longer than anyone expected. But Lithgow received a gift too; that hour sharing

the Wodehouse story with them was a revelation:

Only infrequently had I ever paused

to plumb the mysteries of my peculiar occupation. That night, however,

everything came into focus. Sitting at my parents’ bedside and reading them a

story… came to seem like a distillation of everything my profession is about.

That revelation spurred Lithgow to write his memoir. He has

since performed the story for audiences in his one-man show.

One of the principal defining characteristics of human

beings, besides our opposable thumbs and our inability to resist laughing-baby

videos, is that we are storytellers. From the grand sweep of history to “What

happened at work today?” we are, like John Lithgow, both the actors and the

tellers of tales of our shared humanity. The more uplifting ones have the power

to ease our pain, dissolve our fear, and rejuvenate our atrophied souls.

I have read to my two little

girls every night of their lives not only so the love of books will be deeply

ingrained in them, but so they will connect deeply with stories as a way to

understand life, themselves and the world; so they will know they can always

find wisdom and laughter and solace in them; and so that, perhaps many years

from now when I need it most, they will read to me.

(This article originally appeared here on Acculturated, 3/10/14)